The UK has become the latest country to face questions over its ability to meet national climate commitments.

In a podcast on Friday, Nick Butler, former head of strategy at oil giant BP and a visiting professor at Kings’ College London, said it wasn’t clear how the new government would fulfil its promise of a net-zero electricity and power generation system by the end of the decade, describing the challenge as “really difficult”.

And while the UK has invited doubts by strengthening its pledges, other nations have already begun to backtrack.

Sweden watered down its 2030 targets last year, Australia’s opposition party is pledging to scale back if it gets in, and if Donald Trump is re-elected as the next president of the US, he will exit the Paris Agreement for a second time.

The seriousness of national climate targets will come under further scrutiny over the next six months, as governments must spell out their 2035 targets (Nationally Defined Contributions, NDCs) under the Paris Agreement, ahead of COP30 next year.

Some investors see it as a key opportunity to engage with sovereign bond issuers on the topic.

Aviva, BNP Paribas, Nordea and Robeco are among nearly 30 investors that have been engaging with sovereigns and sub-sovereigns in Australia.

“Investors are buying into countries’ climate pledges without there being any bite if they don’t fulfil them”

Ulf Erlandsson, Anthropocene Fixed Income Institute

The group, which has had nearly 40 meetings with government departments over the past year, has confirmed the “development of the next Australian Nationally-Determined Contribution under the Paris Agreement” is now one of its focus areas.

It has also started working with Japanese policymakers, and is expected to embark on further sovereign engagements shortly.

But Ulf Erlandsson, founder of climate think-tank the Anthropocene Fixed Income Institute, says investors have so far failed to find a way to hold governments accountable for achieving all these commitments.

“Investors are buying into countries’ climate pledges without there being any bite if they don’t fulfil them,” he told IPE.

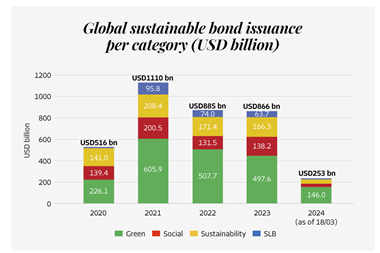

Erlansson argued that the answer lies in sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs), which he described as “a way to contractualise the climate transition”.

SLBs work by tying the interest rate of the bond to whether the issuer achieves or fails on pre-agreed sustainability targets.

Erlandsson suggested that investors and banks should push sovereign issuers in developed, liquid markets to start road-testing SLBs linked to their short-term climate targets – meaning a country would trigger a step-up in coupon if it failed to achieve its 2035 NDC target.

The payouts don’t have to be massive to make the structure effective, Erlansson insisted, because in the context of sovereign borrowing “a couple of basis points still makes a big difference”.

In a paper published today, he argues that to maximise the effectiveness of sovereign climate SLBs, treasuries should be encouraged to issue twin deals: one SLB and one plain-vanilla bond, concurrently, with exactly the same terms.

If all else is equal, it’s possible to isolate the pricing differential driven by the climate component: if investors think the 2035 target will be achieved, they won’t pay much more for SLB notes than ordinary ones; but if they think the country will miss its goals and trigger the step-up, the deal should price much higher in anticipation of the additional income further down the line.

“That would be pretty fantastic because as well as giving investors a chance to hedge against climate risk, and the political volatility of net-zero pledges, it would provide governments with serious information about how the markets view their transition stories,” he said.

Thailand confirmed to the media recently that it was planning to tap the SLB market with a deal tied to its climate targets, and there are reports of upcoming deals from South Africa and Slovenia.

The emergence of national and sectoral transition plans would help investors assess the chance of a country meeting its goals, and therefore calculate the likelihood of a payout under an SLB. Other analysis would be needed on top of that, to identify the key financial, technological and political uncertainties that could hinder success.

“If you’re an investor with a net-zero target, then hopefully you’re already making probabilistic assessments of how likely your portfolio issuers are to align with those goals,” said Erlandsson. “SLBs are just a way of professionalising and financialising that process.”

He noted that “there still needs to be a lot of thinking done” about what a reasonable target would be for a sovereign, and how it should be assessed.

“It’s not easy,” he admitted. “But we’re in finance: it’s not meant to be easy.”

Read the digital edition of IPE’s latest magazine